The Earth Turns

On June 13, 2009, I was working for a startup in Boulder, Colorado, and I took the bus to work every day. The night before I had spent on the internet, carefully following the emerging Iranian election protests.

Revolutions fascinate me. I spent evenings in 2011 following the video livestreams from Occupy Oakland and Occupy Boston later that same year, and on the morning of the 13th I sat on my bus seat glued to the screen of my smartphone, refreshing twitter feeds from Iran, Google News, Facebook.

Malcom Gladwell, unarguably more of an expert on this topic than I, posits that the medium is unimportant: people have been organizing revolutions far before the internet became mainstream. His article about the hierarchical formation of the civil rights movement of the 1960s argues that having twitter or facebook could have hurt the movement by turning it from a well-organized force into a sprawling, ineffective network:

Enthusiasts for social media would no doubt have us believe that King’s task in Birmingham would have been made infinitely easier had he been able to communicate with his followers through Facebook, and contented himself with tweets from a Birmingham jail. But networks are messy: think of the ceaseless pattern of correction and revision, amendment and debate, that characterizes Wikipedia. If Martin Luther King, Jr., had tried to do a wiki-boycott in Montgomery, he would have been steamrollered by the white power structure. And of what use would a digital communication tool be in a town where ninety-eight per cent of the black community could be reached every Sunday morning at church? The things that King needed in Birmingham—discipline and strategy—were things that online social media cannot provide.

(Source)

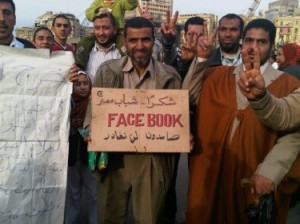

And yet Egypt seems to have benefited from these modern innovations. In this photo from 2011, an Egyptian protester holds a sign thanking Facebook for enabling the revolution. (At least, that’s what the translations have told me. I don’t read farsi myself :P)

And from Gladwell’s October 2010 article (this is four months before “Arab Spring” officially started):

“Without Twitter the people of Iran would not have felt empowered and confident to stand up for freedom and democracy,” Mark Pfeifle, a former national-security adviser, later wrote, calling for Twitter to be nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize

(Source)

Yet Gladwell argues (in 2010) that our view of the revolution is skewed by our own media:

In the Iranian case, meanwhile, the people tweeting about the demonstrations were almost all in the West. “It is time to get Twitter’s role in the events in Iran right,” Golnaz Esfandiari wrote, this past summer, in Foreign Policy. “Simply put: There was no Twitter Revolution inside Iran.” The cadre of prominent bloggers, like Andrew Sullivan, who championed the role of social media in Iran, Esfandiari continued, misunderstood the situation. “Western journalists who couldn’t reach—or didn’t bother reaching?—people on the ground in Iran simply scrolled through the English-language tweets post with tag #iranelection,” she wrote. “Through it all, no one seemed to wonder why people trying to coordinate protests in Iran would be writing in any language other than Farsi.”

(Source)

I remember on the bus that morning in 2009 a constant stream of English-language tweets directly from Iran, and perhaps they were tailored toward me as a westerner, but I can’t imagine they wouldn’t be helpful to anyone in the situation – locations, names, tactics. Shared with the knowledge that the police were watching the stream as well.

The contemporary (her last tweet at the time of this writing is from 5 seconds ago) Egyptian blogger Zeinobia blogs in English, her Twitter feed is almost entirely in Farsi, leaving me to pick out the few English RTs to make sense of the situation. Her 100k followers probably get a lot more meaning from her stream than I do.

The internet moves fast, and it’s helping to accelerate the speed of our lives. Gladwell is probably right, and these revolutions would have happened without Twitter and Facebook, but I think that the Internet is acting as a catalyst to accelerate these movements. The internet is a kind of Central Nervous System for humanity.

Leave a Reply